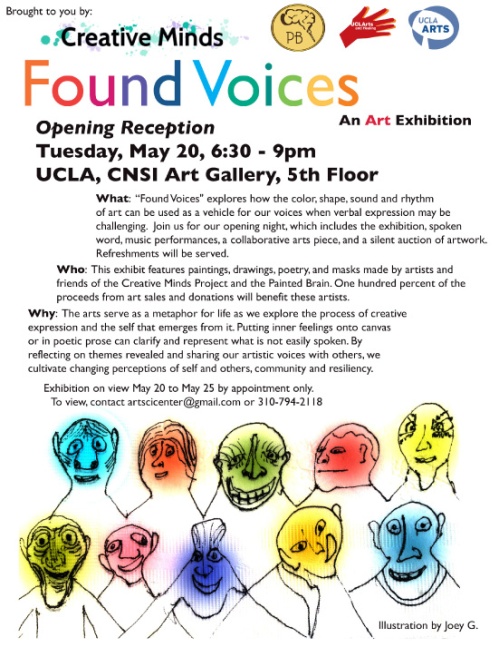

Join us where ART and SCIENCE collide with Art, Poetry & Music at the California NanoSystems Institute, UCLA Art/ Sci + Lab, Gallery, at UCLA CNSI, this coming Tuesday, May 20th, at 6.30-9.00 p.m.

Category Archives: pharmacieuticals

Found Voices: Art Exhibit, Poetry, Music

Posted in addicts, advocate, alternatives, arts, awareness, behavior, brain, community, consumers, culture, groups, healthy lifestyle, human & civil rights, language, mad pride, madness, mental health, perspective, pharmacieuticals, politics, psychiatry/medicine, psychology, research, schizophrenia, self-care, stigma, support, survivors, veterans

Tagged alternatives, Arts, awareness, biological, brain, consciousness, culture, dance, drama, healing arts, holistic, homeless, human rights, love, Mental disorder, mental diversity, mental health, music, planet, Poetry, positive response, psychosis, schizophrenia, social psychology, therapy

When Johnny and Jane Come Marching Home

This is an incredible project started by Dr. Paula J. Caplan , a clinical and research psychologist, and an Associate at Harvard University’s DuBois Institute and a past Fellow at the Women and Public Policy Program in Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. She is the author of: The Myth of Women’s Masochism, They Say You’re Crazy: How the World’s Most Powerful Psychiatrists Decide Who’s Normal, and ten other books. Her articles, essays, and op-eds have appeared in both scholarly and popular publications.

, a clinical and research psychologist, and an Associate at Harvard University’s DuBois Institute and a past Fellow at the Women and Public Policy Program in Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. She is the author of: The Myth of Women’s Masochism, They Say You’re Crazy: How the World’s Most Powerful Psychiatrists Decide Who’s Normal, and ten other books. Her articles, essays, and op-eds have appeared in both scholarly and popular publications.

Thank you for your interest in this work!

Listening is “the art and practice of putting someone else’s speaking, thinking, feeling needs ahead of our own,” wrote Marc Wong in Thank You For Listening.

The Welcome Johnny and Jane Home Project helps veterans heal – and reduces the too-common chasms between veterans and nonveterans – by having one nonveteran at a time simply listen to a veteran from any war. You can become involved by doing one or more sessions, by helping organize others to get involved, or both. Listeners are not therapists, and – except for speaking two sentences – they truly do nothing but listen. However, they do so with 100% of their attention and their whole hearts. Harvard University research has shown that veterans describe this as helpful, and the listeners say it is wonderfully transformative for them.

This is about human connection through the often overlooked but astonishing power of listening. Regardless of the veteran’s politics and the listener’s politics, the sessions are healing.

The three main steps you need to take are becoming familiar with the purpose and guidelines, finding a place to do the session, and finding a veteran who wants to do a session. For more information about how to get involved with the project, click here.

When Johnny and Jane Come Marching Home

“He who sees a need and waits to be asked for help is as unkind as if he had refused it.”

– Dante Alighieri (1265-1321)

Posted in awareness, brain, consumers, deaths, mental health, news, pharmacieuticals, politics, psychiatry/medicine, stigma, support, survivors, veterans

Tagged American Psychiatric Association, brain, compassion, diagnosis, DSM, mental health, pharmaceuticals, psychiatry, stigma, survivor, veterans

The DSM-5: A Dystopian Novel

March/April 2014, By Sam Kriss, from The New Inquiry

The best dystopian literature, or at least the most effective, manages to show us a hideous and contorted future while resisting the temptation to point fingers and invent villains. This is one of the major flaws in George Orwell’s 1984: When O’Brien laughingly expounds on his vision of “a boot stamping on a human face—forever” he starts to acquire the ludicrousness of a Bond villain; he may as well be a cartoon—one of the Krusty Kamp counselors in The Simpsons, raising a glass “to Evil.” Orwell’s satire of Stalinism, or Margaret Atwood’s on the religious right in The Handmaid’s Tale tend to let our present world off the hook a little by comparison. More subtle works, like Huxley’s Brave New World, are far more effective. His Controller, when interrogated, doesn’t burst out in maniacal laughter and start twiddling his moustache. He explains, in quite reasonable terms, why the dystopia he lives in is the best way to ensure the happiness of all—and he means it. Everything’s broken, but it’s not anyone’s fault; it’s terrifying because it’s so familiar.

Great dystopia isn’t so much fantasy as a kind of estrangement or dislocation from the present; the ability to stand outside time and see the situation in its full hideousness. The dystopian novel doesn’t necessarily have to be a novel. Maybe the greatest piece of dystopian literature ever written is Theodor Adorno’s Minima Moralia, a collection of observations and aphorisms penned by the philosopher while in exile in America during and after the Second World War. Even if, like I do, you disagree enthusiastically with his blanket condemnation of all “degenerated” popular culture, it’s hard not to be convinced that what we are living is “damaged life.” It’s not an argument so much as revelation. In Adorno’s bitterly lucid critique everything we take for granted is suddenly revealed in all its hideousness. The world Adorno lives in isn’t quite the same as ours; he’s coming at his subjects from a reflex angle—they’re a bunch of average Joes and Janes, he’s a misanthropic German cultural theorist with a preternaturally spherical head—but his insights are all the more relevant because of this. Something has gone terribly wrong in the world; we are living the wrong life, a life without any real fulfillment. The newly published DSM-5 is a classic dystopian novel in this mold.

It’s also not exactly a conventional novel. Its full title is an unwieldy mouthful: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. The author (or authors) writes under the ungainly nom de plume of The American Psychiatric Association—although a list of enjoyably silly pseudonyms is provided inside (including Maritza Rubio-Stipec, Dan Blazer, and the superbly alliterative Susan Swedo). The thing itself is on the cumbersome side. Over two inches thick and with a thousand pages, it’s unlikely to find its way to many beaches. Not that this should deter anyone; within is a brilliantly realized satire, at turns luridly absurd, chillingly perceptive, and profoundly disturbing.

If the novel has an overbearing literary influence, it’s undoubtedly Jorge Luis Borges. The American Psychiatric Association takes his technique of lifting quotes from or writing faux-serious reviews for entirely imagined books and pushes it to the limit: Here, we have an entire book, something that purports to be a kind of encyclopedia of madness, a Library of Babel for the mind, containing everything that can possibly be wrong with a human being. Perhaps as an attempt to ward off the uncommitted reader, the novel begins with a lengthy account of the system of classifications used—one with an obvious debt to the Borgesian Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge, in which animals are exhaustively classified according to such sets as “those belonging to the Emperor,” “those that, at a distance, resemble flies,” and “those that are included in this classification.”

Just as Borges’ system groups animals by seemingly aleatory characteristics entirely divorced from their actual biological attributes, DSM-5 arranges its various strains of madness solely in terms of the behaviors exhibited. This is a recurring theme in the novel, while any consideration of the mind itself is entirely absent. In its place we’re given diagnoses such as “frotteurism,” “oppositional defiant disorder,” and “caffeine intoxication disorder.” That said, these classifications aren’t arranged at random; rather, they follow a stately progression comparable to that of Dante’s Divine Comedy, rising from the infernal pit of the body and its weaknesses (intellectual disabilities, motor tics) through our purgatorial interactions with the outside world (tobacco use, erectile dysfunction, kleptomania) and finally arriving in the limpid-blue heavens of our libidinal selves (delirium, personality disorders, sexual fetishism). It’s unusual, and at times frustrating in its postmodern knowingness, but what is being told is first and foremost a story.

This is a story without any of the elements that are traditionally held to constitute a setting or a plot. A few characters make an appearance, but they are nameless, spectral shapes, ones that wander in and out of view as the story progresses, briefly embodying their various illnesses before vanishing as quickly as they came—figures comparable to the cacophony of voices in The Waste Land or the anonymously universal figures of Jose Saramago’s Blindness. A sufferer of major depression and of hyperchondriasis might eventually be revealed to be the same person, but for the most part the boundaries between diagnoses keep the characters apart from one another, and there are only flashes. On one page we meet a hoarder, on the next a trichotillomaniac; he builds enormous “stacks of worthless objects,” she idly pulls out her pubic hairs while watching television. But the two are never allowed to meet and see if they can work through their problems together.

This is not to say that there is no setting, no plot, and no characterization. These elements are woven into the encyclopedia-form with extraordinary subtlety. The setting of the novel isn’t a physical landscape but a conceptual one. Unusually for what purports to be a dictionary of madness, the story proper begins with a discussion of neurological impairments: autism, Rett’s disorder, “intellectual disability”. The scene this prologue sets is one of a profoundly bleak view of human beings; one in which we hobble across an empty field, crippled by blind and mechanical forces whose workings are entirely beyond any understanding. This vision of humanity’s predicament has echoes of Samuel Beckett at some of his more nihilistic moments—except that Beckett allows his tramps to speak for themselves, and when they do they’re often quite cheerful. The sufferers of DSM-5, meanwhile, have no voice; they’re only interrogated by a pitiless system of categorizations with no ability to speak back. As you read, you slowly grow aware that the book’s real object of fascination isn’t the various sicknesses described in its pages, but the sickness inherent in their arrangement.

Who, after all, would want to compile an exhaustive list of mental illnesses? The opening passages of DSM-5 give us a long history of the purported previous editions of the book and the endless revisions and fine-tunings that have gone into the work. This mad project is clearly something that its authors are fixated on to a somewhat unreasonable extent. In a retrospectively predictable ironic twist, this precise tendency is outlined in the book itself. The entry for obsessive-compulsive disorder with poor insight describes this taxonomical obsession in deadpan tones: “repetitive behavior, the goal of which is […] to prevent some dreaded event or situation.” Our narrator seems to believe that by compiling an exhaustive list of everything that might go askew in the human mind, this wrong state might somehow be overcome or averted. References to compulsive behavior throughout the book repeatedly refer to the “fear of dirt in someone with an obsession about contamination.” The tragic clincher comes when we’re told, “the individual does not recognize that the obsessions or compulsions are excessive or unreasonable.” This mad project is so overwhelming that its originator can’t even tell that they’ve subsumed themselves within its matrix. We’re dealing with a truly unreliable narrator here, not one that misleads us about the course of events (the narrator is compulsive, they do have poor insight), but one whose entire conceptual framework is radically off-kilter. As such, the entire story is a portrait of the narrator’s own particular madness. With this realization, DSM-5 starts to enter the realm of the properly dystopian.

This madness does lead to some startling moments of humor. One vignette describes in deadpan tones a scene at once touchingly pathos-laden and more than a little creepy: “He rubs his genitals against the victim’s thighs and buttocks. While doing this he fantasizes an exclusive, caring relationship with the victim.” The entry on caffeine intoxication disorder informs us, with every appearance of seriousness, that the diagnostic criteria include “recent consumption of caffeine” along with “1) restlessness 2) nervousness 3) excitement.” There are, occasionally, what seem to be surreal parodies of religious dietary regulations: “Infants and younger children […] eat paint, plaster, string, hair, or cloth. Older children may eat animal droppings, sand, insects, leaves, or pebbles.” What the levity of these moments masks, though, is the sense of loneliness that saturates the work.

The narrative voice of the book affects a tone of clinical detachment, one in which drinking coffee and paranoid-type schizophrenia can be discussed with the same flat tone. Under the pretense of dispassion this voice embodies a whole raft of terrifying preconceptions. Just like the neurological disorders that appear at the start of the book, mental illnesses appear like lightning bolts, with all their aura of divine randomness. Even when etiologies are mentioned they’re invariably held to be either genetic or refer to other illnesses such as substance abuse disorders. At no point is there any sense that madness might be socially informed, that the forms it takes might be a reflection of the influences and pressures of the world that surrounds us.

The idea emerges that every person’s illness is somehow their own fault, that it comes from nowhere but themselves: their genes, their addictions, and their inherent human insufficiency. We enter a strange shadow-world where for someone to engage in prostitution isn’t the result of intersecting environmental factors (gender relations, economic class, family and social relationships) but a symptom of “conduct disorder,” along with “lying, truancy, [and] running away.” A mad person is like a faulty machine. The pseudo-objective gaze only sees what they do, rather than what they think or how they feel. A person who shits on the kitchen floor because it gives them erotic pleasure and a person who shits on the kitchen floor to ward off the demons living in the cupboard are both shunted into the diagnostic category of encopresis. It’s not just that their thought-processes don’t matter, it’s as if they don’t exist. The human being is a web of flesh spun over a void.

With this radical misreading, the American Psychiatric Association is following something of a precedent in the actual psychological professions. Sigmund Freud himself performs a similar feat of ostranenie in his Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, in which he appears to take the position of an alien observer of everyday affairs, noting that “the kiss […] is held in high sexual esteem among many nations in spite of the fact that the parts of the body involved do not form part of the sexual apparatus but constitute the entrance to the digestive tract.” If you’re going to make a properly objective study of human behavior, to some extent you have to disavow your own humanity. You have to ask, why kissing? Why do people press their mouths up against each other? In DSM-5 we can see a perverse mirror image of this kind of estrangement. Freud retreats to a position of inhuman detachment to ask questions. Here, the narrator does it to issue instructions.

The word “disorder” occurs so many times that it almost detaches itself from any real signification, so that the implied existence of an ordered state against which a disorder can be measured nearly vanishes and is almost forgotten. Throughout the novel, this ordered normality never appears except as an inference; it is the object of a subdued, hopeless yearning. With normality as a negatively defined and nebulously perfect ideal, anything and everything can then be condemned as a deviation from it. Even an outburst of happiness can be diagnosed as a manic episode. And then there are the “not otherwise specified” personality disorder categories. Here all pretensions to objectivity fall apart and the novel’s carefully warped imitation of scientific categories fades into an examination of petty viciousness. A personality disorder not otherwise specified is the diagnosis for anyone whose behaviors “do not meet the full criteria for any one Personality Disorder, but that together cause clinically significant distress […] e.g. social or occupational.” It’s hard not to be reminded of a few people who’ve historically caused social or occupational distress. If you don’t believe that people really exist, any radical call for their emancipation is just sickness at its most annoying.

If there is a normality here, it’s a state of near-catatonia. DSM-5 seems to have no definition of happiness other than the absence of suffering. The normal individual in this book is tranquilized and bovine-eyed, mutely accepting everything in a sometimes painful world without ever feeling much in the way of anything about it. The vast absurd excesses of passion that form the raw matter of art, literature, love, and humanity are too distressing; it’s easier to stop being human altogether, to simply plod on as a heaped collection of diagnoses with a body vaguely attached.

For all the subtlety of its characterization, the book doesn’t just provide a chilling psychological portrait, it conjures up an entire world. The clue is in the name: On some level we’re to imagine that the American Psychiatric Association is a body with real powers, that the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual” is something that might actually be used, and that its caricature of our inner lives could have serious consequences. Sections like those on the personality disorders offer a terrifying glimpse of a futuristic system of repression, one in which deviance isn’t furiously stamped out like it is in Orwell’s unsubtle Oceania, but pathologized instead. Here there’s no need for any rats, and the diagnostician can honestly believe she’s doing the right thing; it’s all in the name of restoring the sick to health. DSM-5 describes a nightmare society in which human beings are individuated, sick, and alone. For much of the novel, what the narrator of this story is describing is its own solitude, its own inability to appreciate other people, and its own overpowering desire for death—but the real horror lies in the world that could produce such a voice.

Read: http://www.utne.com/mind-and-body/dystopian-novel-dsm-5-zm0z14mazros.aspx

Posted in addiction, awareness, behavior, brain, community, consumers, human & civil rights, justice, language, madness, mental health, pharmacieuticals, politics, psychiatry/medicine, psychology, schizophrenia, stigma, survivors

Tagged American Psychiatric Association, biological, bipolar, brain, consciousness, diagnosis, disorder, drugs, DSM, hallucinations, imbalance, language change, Mental disorder, pharmaceuticals, social, society, stress

My Mood, My Choice Mad in America

“Men will always be mad, and those who think they can cure them are the maddest of all.” -Voltaire

in Mad in America Science, Psychiatry and Community, Robert Whitiker’s: http://www.madinamerica.com/

My Mood, My Choice by Cyndi Roberts

“People are just as happy as they make their minds out to be.” -Abraham Lincoln

I remember, just four years ago, when I was wrapped up in the grips of depression, that this quote made me very angry. I thought it was so absurd that I was in control of my thinking, that happiness was my choice. At the time, I believed I was my diagnosis— which actually was a misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder— and that I had no control over it. Doctors told me that I was “sick”, that I had a “brain disease”, and that it was just the way it was for me, and the way it always would be. I also endured severe anxiety that was so intense I wouldn’t leave the house most days and fantasized about death as a way to relieve my suffering.

be. I also endured severe anxiety that was so intense I wouldn’t leave the house most days and fantasized about death as a way to relieve my suffering.

I believed those doctors and suffered tremendously and silently for the next twelve years, wrapped up in my many addictions and a lifetime of negative thinking. As chance would have it, I started to feel that something was seriously wrong with me, and consulted a naturopathic physician for help. Blood work revealed that I was unhealthy in every way possible and that I had about six months to live before my liver failed completely. It was overloaded with chemicals and toxins from medications and my addictions. Miraculously, my intuition hadn’t been completely silenced after all.

With nothing left to lose, I’d reached the point at which I had to make a choice: to fight, or to give up. Though things seemed to not be going my way, I decided to take back control and make drastic changes in hopes to survive. That’s when yoga, meditation and nutrition came into my life, but first, I had to find a doctor to help me get off the medication I was currently on. The doctor I’d been seeing had refused to help, so I printed out a list of doctors covered by insurance and made some calls. Each nurse I spoke with wanted to help but doubted the doctor would take my case on. Weeks and thirty-seven “Nos” later, doctor thirty-eight finally said “Yes”. This doctor was not covered by insurance but had a sliding scale payment plan available, which made it possible for me to see him. The painful journey of detox began and so did my intense study of meditation, yoga and nutrition.

Up until this point in my life, I was searching for balance, peace and happiness outside of myself rather than looking inside, where I know today that it really resides. Yoga and meditation allowed me to journey inward and take a look at my internal world. Through daily yoga and meditation practices, I began to get to know myself better and discovered the way my brain worked. I uncovered a stream of negative thinking about myself, others, and the world around me. I began to see that these thoughts made me feel terrible and would often spark more negative thoughts and depressed or anxious feelings. With what I learned from meditation, I began to notice and be aware of my thinking, and then my moods. I learned to become the observer of not only my thoughts, but also my emotions.

continued here: http://www.madinamerica.com/2013/08/mood-choice/

Posted in addiction, advocate, alternatives, awareness, behavior, brain, change, community, consumers, culture, human & civil rights, language, mad pride, mental health, perspective, pharmacieuticals, politics, psychiatry/medicine, psychology, self-care

Tagged awareness, Bipolar disorder, culture, diagnosis, Health, human rights, imbalance, Mad in America, Meditation, Mental disorder, mind, politics, psychiatry, social, stigma, stress, survivor, Yoga

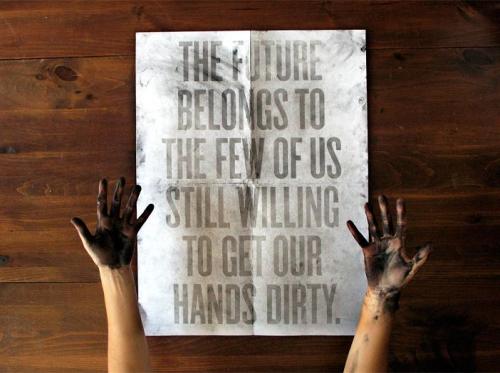

THE FUTURE BELONGS TO THE FEW OF US STILL WILLING TO GET OUR HANDS DIRTY

WE ARE CURRENTLY COLLECTING STORIES FOR A BOOK WITH THE THEME:

READ ALL ABOUT IT: THE UNFORGETTABLE HARM AND PAIN WE EXPERIENCED FROM THE DSM

IF YOU OR ANYONE YOU KNOW IS INTERESTED IN CONTRIBUTING, PLEASE EMAIL US AT: ECOEDUCATE@GMAIL.COM

THANK YOU FOR YOUR INTEREST AND SOLIDARITY

Posted in advocate, alternatives, awareness, behavior, consumers, deaths, justice, mad pride, mental health, perspective, pharmacieuticals, psychiatry/medicine, self-care, stigma, support, survivors

Tagged American Psychiatric Association, awareness, disorder, DSM, Mental disorder, mental diversity, mental health, psychiatry, stigma, survivor

Which “disorders” Do You Suffer From?

In Dr. Mercola’s article, the New England Journal of Medicine exposes the new DSM for making “Grief” a Psychiatric Illness. Dr. Mercola writes-

- Do you shop too much? You might have Compulsive Shopping Disorder.

- Do you have a difficult time with multiplication? You could be suffering from Dyscalculia.

- Spending too much time surfing the Web? It might be Internet Addiction Disorder.

- Spending too much time at the gym? You’d better see someone for your Bigorexia or Muscle Dysmorphia.

It’s almost impossible to see a psychiatrist today without being diagnosed with a mental disorder because so many behavior variations are described as pathology. And you have very high chance – approaching 100% — of emerging from your psychiatrist’s office with a prescription in hand. Writing a prescription is, of course, much faster than engaging in behavioral or lifestyle strategies, but it’s also a far more lucrative approach for the conventional model. Additionally, most practitioners have yet to accept the far more effective energetic psychological approaches.

The branding of various forms of normal human emotions as “mental illness” has been a Big Pharma cash cow for years. According to marketing professional Vince Parry in a 2003 commentary called “The Art of Branding a Condition“:

“Watching the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) balloon in size over the decades to its current phonebook dimensions would have us believe that the world is a more unstable place today than ever.”… Not surprisingly, many of these newly coined conditions were brought to light through direct funding by pharmaceutical companies, in research, in publicity or both.”

And if that’s not damning enough, a former chief of the American Psychiatric Association admitted that some of the “mistakes” the APA made in its diagnostic manual have had “terrible consequences,” which have mislabeled millions of children and adults, and facilitated epidemics of mental illness that don’t exist.

Read more here

Posted in behavior, consumers, human & civil rights, language, mental health, pharmacieuticals, politics, psychiatry/medicine

Tagged American Psychiatric Association, culture, Diagnostic & Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), Dyscalculia, Internet addiction disorder, Mental disorder, mental health, Muscle Dysmorphia, pharmaceuticals, psychiatry

Be Wary of the American Psychiatric Association

by Dr. Keith Ablow, published on May 14, 2012 by http://www.foxnews.com

Dr. Keith Ablow is a psychiatrist and member of the Fox News Medical A-Team. Dr. Ablow can be reached at info@keithablow.com.

The American Psychiatric Association (from which I resigned in protest, some time ago) is at it again—making up, then retracting, new diagnoses that their committees generate and debate. It’s as if those committees have some sort of microscope trained on humanity, identifying new pathologies and yelling, “Voila! We have found another illness! Behold the mind malady on the slide!”

In this case, while preparing to publish its big seller (and huge profit center), the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders V (DSM-V)—organized psychiatry’s compendium of known psychiatric illnesses—the powers that be at the APA have decided to remove from its latest revision of the manual a few diagnoses they thought they would include: “attenuated psychosis syndrome” and “mixed anxiety depressive disorder.” They are, however, sticking with their notion of jettisoning from the DSM-V, the diagnosis of Asperger’s Syndrome, while picking up one they call, “Autism Spectrum Disorder.”

In this case, while preparing to publish its big seller (and huge profit center), the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders V (DSM-V)—organized psychiatry’s compendium of known psychiatric illnesses—the powers that be at the APA have decided to remove from its latest revision of the manual a few diagnoses they thought they would include: “attenuated psychosis syndrome” and “mixed anxiety depressive disorder.” They are, however, sticking with their notion of jettisoning from the DSM-V, the diagnosis of Asperger’s Syndrome, while picking up one they call, “Autism Spectrum Disorder.”

This would be really funny, if it weren’t really dangerous. The DSM-V will be used by hundreds of thousands of clinicians who may think that they are understanding their patients better, or treating them more expertly, by labeling them with one of 300 or so disorders listed in it, then matching medications to those supposedly genuine labels. But those labels aren’t driven just by science, but by political, economic and commercial forces within the American Psychiatric Association that may have nothing to do with the wellbeing of patients – or with reality.

The labels in the DSM-V (like the Diagnostic and Statistical Manuals that came before it) have really become little more than the roadmap by which psychiatrists chase both insurance reimbursement and applause from special interest groups who lobby—sometimes very effectively—for one diagnosis to be included, or another to be removed.

See, without a numbered diagnosis—such as number 312.30 Impulse-Control Disorder Not Otherwise Specified or number 307.47 Nightmare Disorder (formerly Dream Anxiety Disorder)—insurance companies won’t write a check to social workers, psychologists or psychiatrists who help people who have terrible outbursts or can’t sleep. Without a numbered diagnosis, pharmaceutical companies can’t get an FDA indication to use a particular medicine for that diagnosis. And without a numbered diagnosis, psychiatric wards can’t get paid to treat patients who hear voices or see visions or are dependent on heroin.

Never mind that splicing and dicing the range of human experience into a recipe book of contrived illnesses does damage to the miraculous healing power of empathy, which just happens to be psychiatry’s birthright. Never mind that creating a constantly-evolving dictionary of disorders wrenches the wonderful tools of psychotherapy and psychiatric medications into a realm of fiction that can paralyze them—like, for instance, the time that the American Psychiatric Association removed Ego-Dystonic Homosexuality from the DSM, essentially making the case that people who have sexual impulses they themselves dislike and wish to resist need no help at all and are pretty much normal. Similarly, now, for those with Asperger’s Disorder, which no longer exists as a distinct entity because someone on some committee convinced other people on that committee that it just doesn’t.

So, there. Take two of those, and call me in the morning.

Mind you, this is the same organization purporting to represent American psychiatrists while refusing to say just what percentage of those psychiatrists belong to it. It is the same organization that has presided over the near decimation of insight-oriented psychotherapy—still far-and-away the best technique, in capable hands, that we have to truly heal those suffering with mental disorders.

We in America face an epidemic of fiction—manipulations of the truth on a scale never before known, fueled by technology and media. This epidemic threatens to rob us of ourselves—what we truly think and truly feel and truly know as fact. And this epidemic has clearly infected the American Psychiatric Association, which puts them on the wrong side of Truth, and puts patients at needless risk.

Read more: http://www.foxnews.com/health/2012/05/14/be-wary-american-psychiatric-association/#ixzz1v0W43vSX

Posted in advocate, brain, consumers, culture, justice, mental health, pharmacieuticals, politics, psychiatry/medicine, stigma

Tagged brain, diagnosis, DSM, pharmaceuticals, psychiatry, stigma